SELECTED ARTICLES

Over the years I have written for The New York Times, The Atlantic, Salon.com, Wilson Quarterly, the ACM, and assorted sketchy websites (like this one). These days I do most of my writing over on Substack. For a full bibliography, see my CV.

Herbert Haviland Field and the Secret History of the Modern Intelligence Agency

New research reveals how AI can alter human memories—and reshape our sense of reality

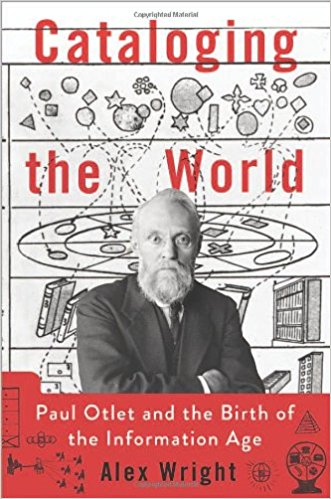

The strange tale of two unlikely quadrupeds that helped shape the modern information age.

A forgotten tale of a tramp printer down on his luck.

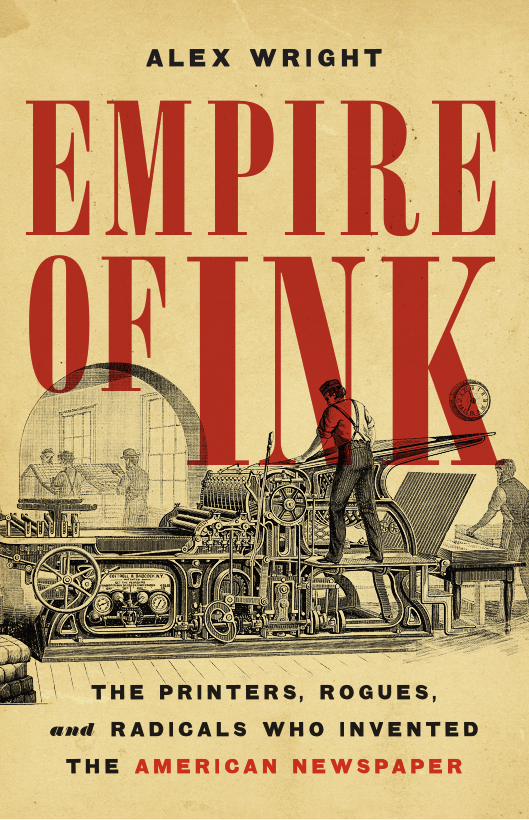

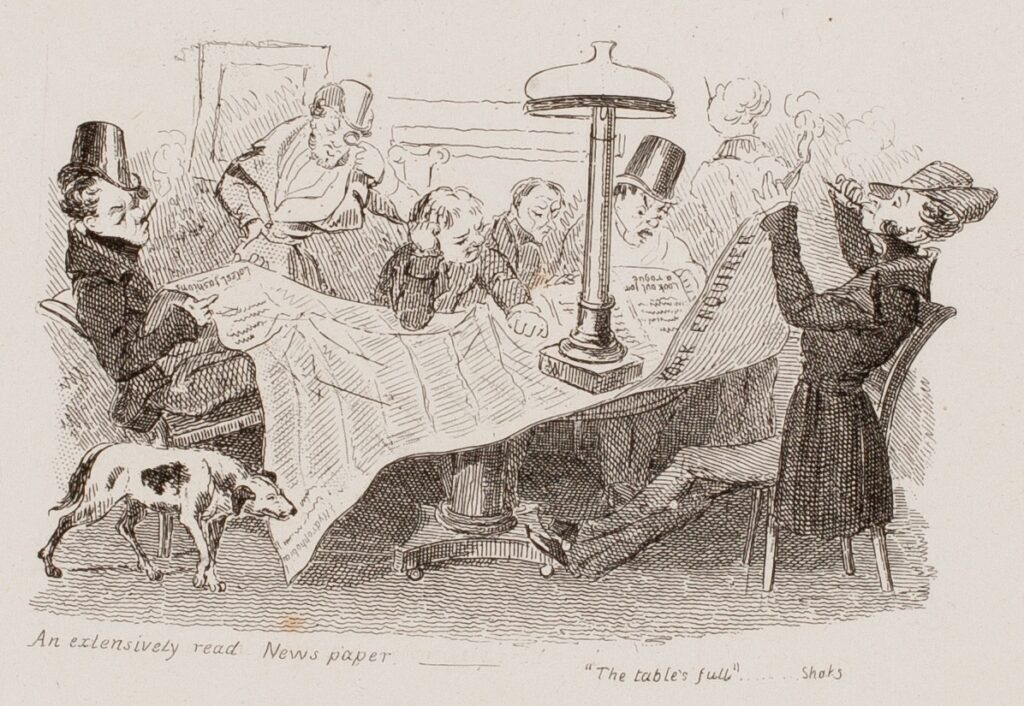

Before chatbots and content farms, the penny press was generating slop at industrial scale. What the nineteenth century can teach us about today’s AI crisis — and what might come next.

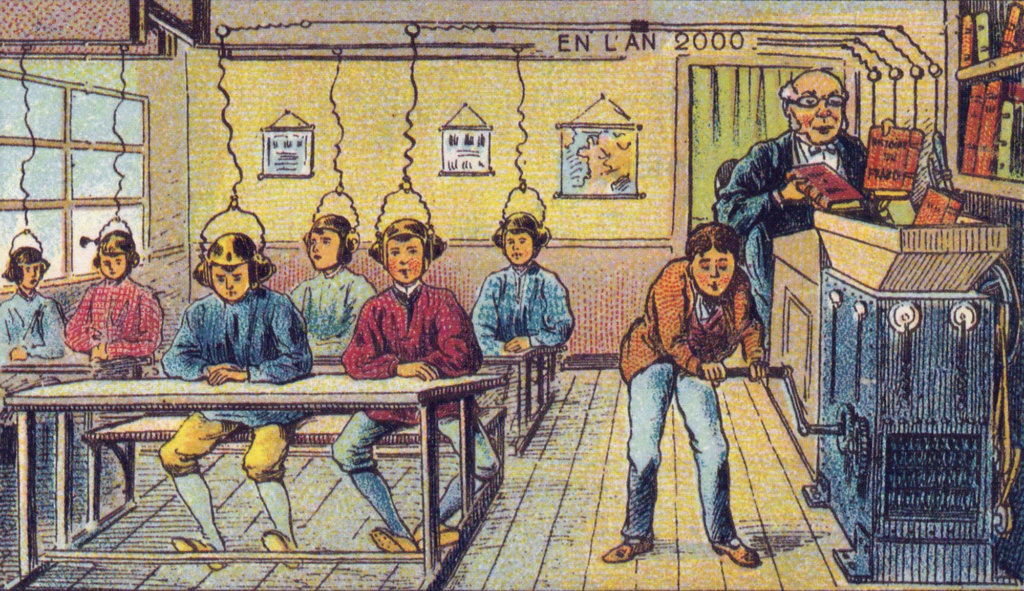

We tend to think of the “infinite scroll” as a by-product of the smartphone era. But its roots stretch deep into the nineteenth century—a period that has a lot to teach us about today’s attention economy and the rise of LLMs.

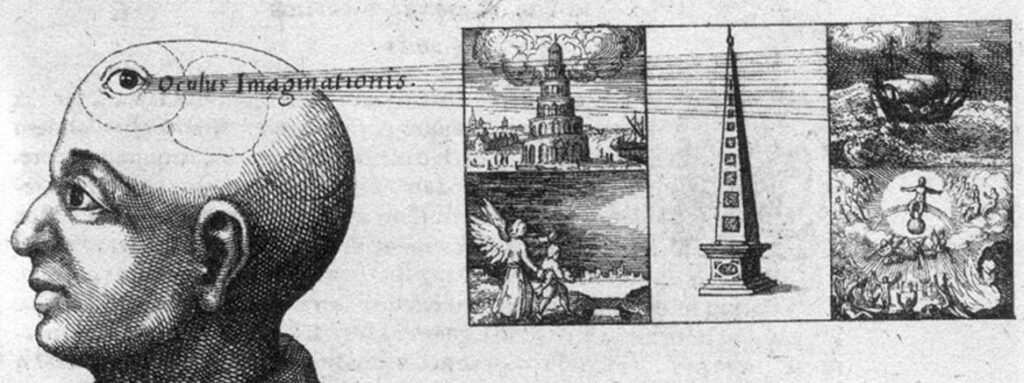

In 1532, a charismatic inventor named Giulio Camillo promised a technological breakthrough: a device that would unlock the wisdom of the ages and make it available to the average person.

He raised money, impressed the cognoscenti, and dazzled the crowds – and failed to deliver a working product. Sound familiar?

I’m launching a new Substack newsletter, exploring the deep history of the digital age: the forgotten people, inventions, and ideas that continue to shape how we think and communicate.

This week I shared a few remarks at Belgium’s KIKK Festival on new directions in AI-enabled historical research, alongside CUNY’s Peter Aigner. Here’s a rough sketch of my talk.

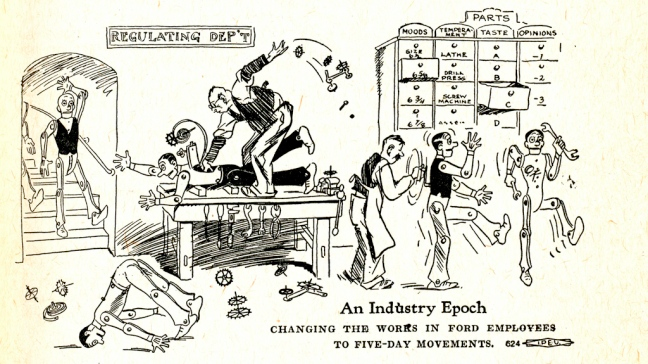

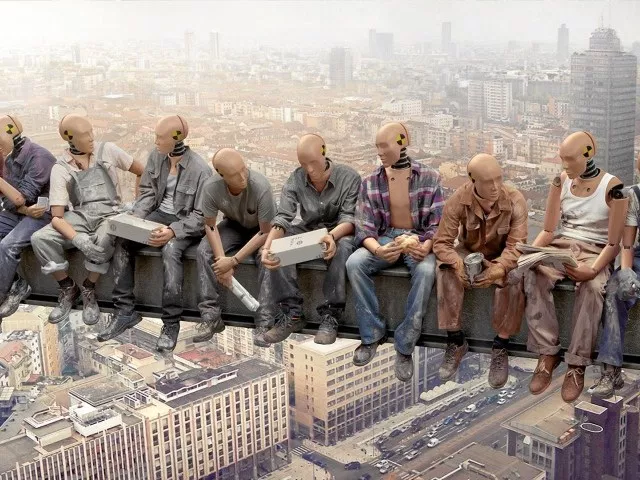

What makes work meaningful, or meaningless? Exploring pathways for UX practitioners to evolve their practices towards more fulfilling, socially engaged ways of working.

UX practice stands at a crossroads, as practitioners increasingly struggle with the escalating pressures of industrial capitalism. How might we envision alternative futures for more a post-capitalist version of UX practice?

In an increasingly metrics-driven business climate, UX practitioners face escalating pressures to deliver small-scale results. Is there a better way?

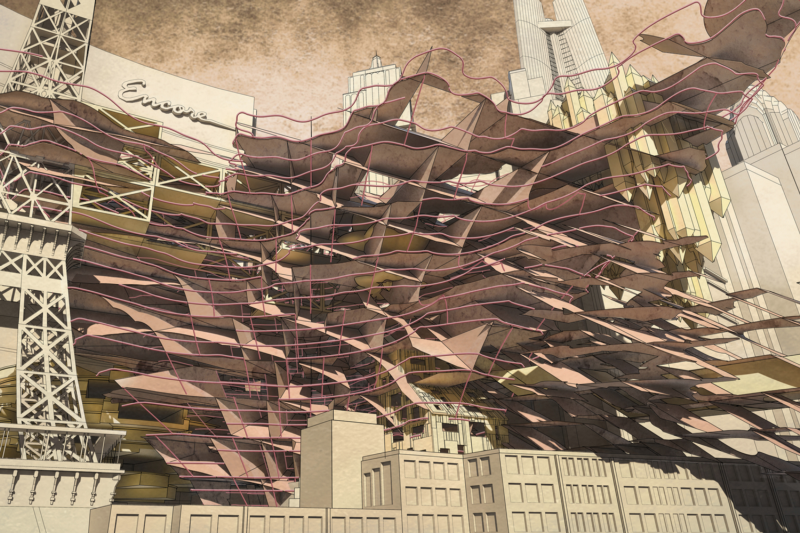

Reflections on teaching a summer course in Design Futures at the School of Visual Arts in NYC.

Reflections on a ten-day course in Transition Design at Schumacher College in the UK.

Recapping a workshop on the future of design education at the 2018 IxDA Education Summit in Lyon, France.

What does it mean to do “meaningful” work? According to a recent MIT study, most of us find meaning in our professional lives in highly individual and idiosyncratic ways: one person’s tedium is another’s labor of love.

In his 1905 novel A Modern Utopia, H.G. Wells imagined a future world in which a small group of highly skilled creative workers wielded enormous power over the rest of society. He dubbed this new breed of elite professionals the “Samurai.”

Good work uses no thing without respect, both for what it is in itself and for its origin …. It does not dissociate life and work, or pleasure and work, or love and work, or usefulness and beauty. — Wendell Berry

As the global network continues to shrink the distance between producers and consumers, the global economy is also beginning to respond to a set major systemic shocks: climate change, growing income inequality, mass migration, and the rise of populist right-wing nationalism, to name a few.

Search engine developers are moving beyond the problems of document analysis, towards the elusive goal of figuring out what people really want.

Leading roboticists are teaming up with thespians to produce new and unexpected forms of theatrical performance.