The Secret History of Hypertext

May 22, 2014

The Atlantic just published my essay on "The Secret History of Hypertext," an exploration of early European precursors to the Web in the era before Vannevar Bush famously proposed the Memex in 1945.

This article draws on material from my book, but I wanted to write an original piece that focused squarely on Bush's legacy, given his lasting influence over the trajectory of post-WWII computing. And the Atlantic seemed like the ideal venue, given the magazine's historic role in publishing Bush's "As We May Think."

Bush's essay is a beautifully crafted piece of technological soothsaying. But, as I suggest here, its influence has obscured the contributions of pioneers like Paul Otlet and H.G. Wells, who were thinking along the same lines well before Bush, and who have been largely overlooked in the traditional Anglo-American version of computing history.

Here's the full shpiel.

Cataloging the World

March 21, 2014

I'm pleased to announce the upcoming release of my next book, Cataloging the World: Paul Otlet and the Birth of the Information Age, to be published in June 2014 by Oxford University Press.

This book has been in the works (off and on), for more than twelve years, ever since I first stumbled across an article by Boyd Rayward that referenced an obscure Belgian bibliographer who envisioned something like the Internet in the 1930s. In the years since then, I have found myself gradually drawn in by the legacy of this brilliant, enigmatic, and at times maddeningly difficult character.

Otlet's work--largely overlooked in the traditional Anglo-American history of computing--offers a provocative vision of an alternative networked world, one driven not by private enterprise but by a new international entity dubbed the Mundaneum, a kind of central intellectual cortex intended to connect the world's governments, universities, museums, libraries, and other institutions into a unified intellectual whole, all available to anyone in the world, "from the comfort of his armchair."

If you're interested in learning more, allow me to recommend the newly launched book website.

Sketchnoted

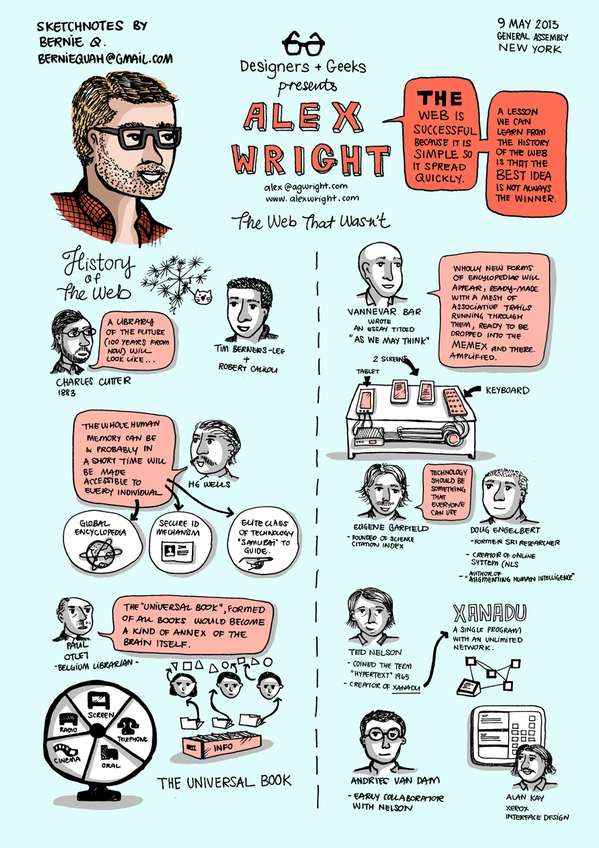

May 22, 2013

Thanks to the fabulously talented Bernie Quah for this Sketchnote version of my recent talk at Designers + Geeks NYC:

It's great to see such a fun, playful treatment of the talk. Given that Bernie turned this around on the fly while I was talking, she can surely be forgiven the odd typo; just for the record: it's Vannevar Bush (not "Bar") and Doug Engelbart with an "a"; and the Eugene Garfield bubble should probably point to Ted Nelson. But these are minor quibbles. All in all she did a fantastic job of capturing the gist of my talk.

Thanks again to Bernie for giving me permission to post this, and to Joe Robinson at Designers and Geeks for inviting me over in the first place.

Conferencing

November 23, 2012

I've been enjoying the chance to get back on the conference circuit again over the past couple of months, after a fairly long hiatus (two kids in diapers have a way of conspiring to keep you at home). There hasn't been much time to reflect on any of it, though, but now that I have a few moments of post-Thanksgiving lull I thought I would try to capture a few highlights:

Brooklyn Beta

I walked a few blocks down the street to the Invisible Dog for the third installment in Cameron Koczon and Chris Shiflett's impossible-to-pin-down three-day happening. It takes no small amount of hubris to hold a conference with no pre-announced agenda or speaker list, but somehow they manage to keep selling it out and delivering on increasingly high expectations. Highlights for me included the sheer badassery of Aaron Draplin's opening talk, in which he somehow managed to combine cutting sarcasm about the crappiness of so much modern design with heart-on-his-sleeves passion for the human potential of creative work; Newark mayor Cory Booker's unexpectedly inspired talk on the possibilities of networks to enhance civic participation; the Onion's Baratunde Thurston on the importance of afternoon whiskey and Location-Based Racism; and the chance to meet Ted Nelson, the iconoclastic and famously curmedgeonly genius without whom the Web might never have happened.

ASIS&T

I took the bus down to Baltimore in the pre-Sandy rainstorms to attend a

day-long conference on the history of information science. In

contrast to the hipster-hacker vibe of Brooklyn Beta, this was a more

serious and staid academic crowd (then again, I tend to be on the serious and staid end of the spectrum myself). In any case, the

presentations were mostly excellent, if a bit on the white-papery side. Boyd Rayward gave an excellent keynote, laying out a sweeping history of how information science has evolved over the years in what he characterized as three successive eras (the print age following Gutenberg; the pre-digital era before WWII; and the current age of ubiquitous technology); Michael Buckland introduced the

forgotten photography pioneer Lodewyk Bendikson;

and Charles Van Den Heuvel gave a solid overview of Donker Duyvis, the often-overlooked

successor to Paul Otlet. The major highlight for me was dinner with

Charles and Boyd, where they regaled me with their encyclopedic knowledge

of Otletiana over Baltimore seafood and one or two too many glasses of wine.

UX Brighton

In early November I visited my old home town and spent a day taking part in Danny Hope's fast-growing UX conference. He put together a provocative lineup of speakers to talk about the past and future of UX design, including: Ben Bashford on the role of empathy in designing for connected devices; Jim Kalbach on innovation; Mike Kuniavsky on the coming confluence of the Maker movement and Web analytics; and Karl Fast on embodied cognition (the best talk of the day, hands-down); and, well, me.

World Usability Day

From Brighton I trekked out to Graz to teach a half-day workshop on user research, thanks to event coordinator Hannes Robier, then participated in an evening conference with an interesting mix of European UXers. Also enjoyed the chance to meet some of the faculty in the interaction design program at the Graz University of Technology, including Keith Andrews and Konrad Baumann, followed by the chance to sample some of the best white port I have ever had the pleasure of tasting at the Buschenschank Labanz in the foothills of southern Austria.

That was more than enough conferencing for one season. It was a fun ride, but I'm long since ready to settle back down for a bit. There's a deadline looming, and it's long since time for me to get back to work.

Brighton-bound

October 21, 2012

I'm looking forward to attending UX Brighton in early November. For me, this is a bit more than just another Web conference; it's also a kind of homecoming.

From 1978 to 1980, I lived in Brighton while attending school at the long-defunct St. Wilfrid's down the road in Seaford. For two years I led the full-on Tom Brown lifestyle - school tie, sweater, goofy shorts and all. When I wasn't boarding at school I spent a fair bit of time wandering around my adopted hometown - roaming the old amusement piers where the old folks fed their pensions into the penny slot machines, knocking around the crumbling waterfront promenade, and rummaging for washed-up salvage on the abandoned beach past the marina. My major Brighton claim to fame came in 1979, when I watched from the sidewalk while they filmed Quadrophenia.

Somehow it seems fitting that the talk I'll be giving is on the history of hypertext, looking at some of the early precursors to the Web in search of interesting ideas left by the historical wayside. I've always felt like I probably left some of my pre-adolescent self in Brighton - and while of course you can't go home again - I'm hoping that I may yet stumble across a few misplaced memories left somewhere by the sea.

Robot Theater

July 6, 2012

The Times' Weekend Arts section is running my story on the emerging intersection of theater and robotics. This was a challenging piece to write; my theater career ended over three decades ago (when I was Chris Kulp's understudy for Tales of a Fourth Grade Nothing); and everything I know about robotics I pretty much learned from watching bad sci-fi movies. So it was humbling to watch a group of kids at New Albany High School performing their own original scripts and programming their Bioloid robots to hit their marks. I also enjoyed the chance to interview smart folks like Bill Smart, Annamaria Pileggi, David Saltz and Heather Knight, whose pal Data may just be the robotic answer to Lenny Bruce.

What I'm Up To These Days

June 8, 2012

Blogging has been painfully slow around here for the past few months (if not, well, years), but life seems to have slowed down enough on this lazy Friday afternoon that I thought I would take a moment to let the Internets know what I've been doing with myself lately.

Mostly, I've been working on my next book. I generally subscribe to Hemingway's advice that it's bad luck to talk too much about books you haven't written yet, but word seems to have trickled out here and there, so I thought I might as well go on the record. Briefly, I'm writing a book about Paul Otlet and the early history of the modern information age. That's about as much as I'm ready to say about it just yet, but if you're interested in hearing more about it as the book gets closer to publication, feel free to drop me a line at alex at alexwright dot org.

In other - far more important news - my wife and I recently welcomed our second son Elliot. He was born at a hearty 10 lb 5 oz (can you say, Daddy's boy?) and has been settling into his new world in Boerum Hill, Brooklyn. But not for long: We're on the verge of closing on a condo in Park Slope later this summer. Because, you know, Park Slope doesn't have quite enough bearded men pushing strollers around the neighborhood while they try to finish their books.

Elsewhere, I'm still plugging away at the Times, where we have a few interesting irons in the fire (some of which should come to light early next year). But for now, I'm getting ready to cash in my paternity leave to focus on the aforementioned book, baby and Brooklyn-ing.

More to come on all of the above, sooner or later. In the meantime, allow me to recommend turning off the WiFi and enjoying the summer.

Linotype: The Film

February 7, 2012

Last week I enjoyed the chance to see the premiere of Linotype, Doug Wilson's new documentary about the automated typecasting machine that revolutionized the twentieth-century printing industry.

I have been fascinated with the Linotype for years, ever since I had the chance to use one briefly at the Firefly Press (whose proprietor John Kristensen makes an appearance in the film). When I first got wind of this film, however, I couldn't help but wonder how they would a) find a market for it, and b) make an interesting story out of an antiquated machine that has long since outlived its usefulness.

As to the first question, I was pleased to see a full house for the screening at SVA, including host Steven Heller who conducted a Q&A with the filmmakers afterwards. A roomful of type geeks may not a blockbuster make, but at least these guys found enough of a following out there to get the film made (apparently with a substantial boost from Kickstarter). Here's hoping that momentum continues to build for them.

As to the question of interestingness, the film more than surpassed my admittedly modest expectations. Wilson wisely avoided the stultifying conventions of traditional historical documentary, focusing instead on interviewing a handful of living, often gloriously eccentric modern Linotype enthusiasts: the 85 year-old deaf typecaster in Iowa, the hipster typecaster in Brooklyn, and the self-taught son of a junkman turned founder of the only Linotype school in the country. The film makes a compelling case for these artisans as artists, toiling in noble anonymity just as their predecessors did for the better part of a century, bringing the printed word to life for generations of readers.

The breakout star of the film may just be Carl Schlesinger, the retired New York Times Linotype operator who had the foresight to shoot some footage of the last day of the Times' Linotype, ultimately released in the late 1970s as a documentary called Farewell Etaoin Shrdlu (and the source of some invaluable footage for this one). Carl attended the screening, and afterwards joined with the other retired Linotype operators in attendance to receive a long-deserved standing ovation.

"Linotype: The Film" Official Trailer.

Crazy Wisdom

December 16, 2011

Earlier this week I finally had the chance to see Crazy Wisdom, Johanna Demetrakas' long-awaited documentary about Chogyam Trungpa Rinpoche, attending a screening at the Rubin Museum followed by a Q&A with Robert Thurman.

In the spirit of full disclosure, I should acknowledge having made a couple of small financial contributions to this project while the filmmakers were trying to get it off the ground. And having spent a fair amount of time in and around the Shambhala community, I can hardly claim to be an impartial reviewer. Like countless other people, I have been captivated by the depth and profundity of Trungpa Rinpoche's teaching. That said, I have never felt obliged to tow any particular party line about some of the more controversial aspects of his legacy: the prodigious drinking, sexual escapades and the sometimes cult-like atmosphere that sprang up around him. And so I have often found myself wrestling with this film's central question: How could an ostensibly enlightened being act this way?

Alas, anyone approaching this film hoping to form some kind of solid judgment about Trungpa Rinpoche will likely come away disappointed. And I suspect that's more-or-less what Demetrakas intended. While the film certainly veers towards presenting Trungpa Rinpoche in a favorable light - I think the Times was probably right to opine that it "loves its subject too well" - it never descends into outright hagiography. And I was glad to see the film doesn't shy away from addressing some of the troubling aspects of his life, although it does perhaps skate past a few of the more shocking episodes (the Great Naropa Poetry Wars come to mind). Then again, it probably would have been easy enough to gather several films' worth of outlandish stories about Trungpa Rinpoche, without ever getting to the point of explaining why he really mattered: namely, his teaching.

The film does a wonderful job of capturing Trungpa Rinpoche at his luminous best in some of his early lectures; I only wish we had seen more of him in the act of teaching. Instead, the film leans heavily on the present-day recollections of his close students, who of course tend to remember him fondly; it certainly would have been interesting to hear at least a couple of dissenting views. For the most part, however, Demetrakas manages to steer clear of the pat explanations that one sometimes hears around the Shambhala community: that every single thing he did was enlightened activity, that such a realized master cannot be judged in terms of conventional morality, or that he somehow took on the neuroses of his students. While there might well be some truth to those perspectives, they also strike me as suspiciously lazy arguments.

I prefer to think of Trungpa Rinpoche's life as a kind of koan, one that doesn't lend itself to easy answers or fixed views. So I was glad to hear Pema Chodron and Diana Mukpo's frank admissions that they found him inspiring and, at times, baffling. This is more-or-less how I feel about him myself. And while I felt the film could have struck a more even-handed note, nonetheless I admired the way it managed to leave his legacy open to contemplation rather than trying to solidify around a particular interpretation.

In the follow-on Q&A session, Robert Thurman rose to a daunting occasion, expressing his admiration for Trungpa's gifts in no uncertain terms - singling out Cutting Through Spiritual Materialism

in particular - while declining to offer any particular excuses for his behavior. Thurman mentioned that he had originally been assigned to be Trungpa Rinpoche's English tutor in India in the early 1960s before unexpected circumstances intervened, and they would not meet in person until many years later in the 1970s; I couldn't help but wonder whether things might have played out differently for either man if they had they managed to forge a connection earlier in their lives.

In response to a question about whether Trungpa Rinpoche may have fallen victim to "self-deception" in his relation to alcohol, Thurman met the elephant in the room head-on, saying that he felt Trungpa Rinpoche may indeed have deluded himself about his alcohol use. He also suggested that some of his students may have borne some responsibility as enablers, arguing that students sometimes have an obligation to "go beyond" the guru yoga practice of viewing the teacher as an enlightened being to recognize the earthly needs of a fellow human being in danger (in fairness, the film did point out that a few of his closest students pleaded with him repeatedly to curtail his drinking). He likened the situation to letting the Dalai Lama get behind the wheel of a car: the student would be foolish to assume that his teacher's bad driving amounted to enlightened activity, and in fact a truly devoted student would probably have an obligation to intercede.

There was an interesting back-and-forth with one of Trungpa Rinpoche's former students in the audience, who asked whether it was perhaps necessary for him to die young (like his close friend Suzuki-roshi) in order for the teachings to fully blossom in the West. Thurman acknowledged that possibility, but also likened that argument to the rationale you sometimes hear that the Chinese did the world a favor by invading Tibet, because it triggered the spread of Tibetan Buddhism to the West; he challenged that perspective, suggesting that Tibetan Buddhism might well have found other routes to the West without Tibetans having to pay such an excruciating price.

Another questioner asked whether Trungpa's drinking could be seen as a lesson in accepting and even embracing one's own human frailties. While acknowledging the Buddhist point of view that we are all in some sense already enlightened, Thurman took exception to the "I'm OK/You're OK" interpretation of Buddhism, claiming for a moment to speak on behalf of Trungpa Rinpoche when he told the student (and I'm paraphrasing here): "Yes, you're perfect, and you could also use a little improvement."

Amen to that, sir.

Winnebago Man

October 22, 2011

On a Friday night Netflix whim, we punched up Winnebago Man, Ben Steinbauer's 2010 documentary about Jack Rebney, the famously pissed-off RV spokesman whose outtake reel attracted a devoted underground following among the film school set and, more recently, across the Intertubes.

On a Friday night Netflix whim, we punched up Winnebago Man, Ben Steinbauer's 2010 documentary about Jack Rebney, the famously pissed-off RV spokesman whose outtake reel attracted a devoted underground following among the film school set and, more recently, across the Intertubes.

What seems like a thin premise for a documentary - tracking down the real life Rebney, twenty years on - turns out to be a surprisingly engaging journey into one man's search for authenticity.

When Steinbauer eventually finds Rebney - living far off the grid in a mobile home near the foot of Mount Shasta - the old man presents himself as a kind of forest yogi, leading a simple life with his dog named Buddha and speaking in tranquil, reflective tones as he looks back with bemused detachment on his former self.

Ben goes away disappointed, wondering whether the oddball character he had hoped to find was just a phantom of his YouTube-fueled imagination.

Just when the film seems on the verge or petering out, it takes a refreshing turn for the weird. Jack calls back to make a confession: he was faking the whole peace-and-love bit. The real Rebney, as it turns out, is every bit the crochety old sonofabitch that Steinbauer imagined. Ben returns to get the real story, and Jack in turn sets out to make his would-be biographer's task close to impossible. As Jack gets more and more difficult, the movie gets better and better.

There's a Buddhist saying that if one wants to progress quickly on the spiritual path, it's best to study with a wrathful master. Steinbauer seems to have found the perfect teacher in Rebney, whose initial attempt at projecting a Yoda-like facade of peace and calm stands in sharp contrast to the authentic pain-in-the-ass that manifests in the second half of the film.

When the story culminates with Rebney making an appearance at a film screening in San Francisco, he rises to the occasion. Bantering with the crowd, he comes across as endearingly pissed-off, like everyone's cranky grandfather. He seems to have found a way to befriend his anger, not by suppressing it but by inhabiting it fully, and inviting everyone to enjoy the spectacle. And the crowd loves him for it.

Chogyam Trungpa Rinpoche's once suggested that the sure

sign of realization is the willingness to make a fully display of one's neuroses. By that standard, the Winnebago Man may just be a true yogi after all.

And now, a word from Jack:

A Week in Mailer Country

June 28, 2011

Norman Mailer once described Provincetown as "the wild west of the east." And while the town has doubtless changed much in the sixty years since Mailer first roamed the dunes - drinking, brawling and screwing his way around town, while completing some of his best work along the way - the place still retains some of the loose, wild energy that has long attracted artists, writers and other misfits to its looping shores.

This was my first time here, so I felt particularly fortunate that my introduction should come by way of the Norman Mailer Writers' Colony, where I've spent the past week participating in a workshop on historical narrative with the brilliant and gregarious Charles Strozier.

Having admired Mailer (warts and all) for many years, I enjoyed spending a week in his old living room in the company of other writers, working out our various kinks while sitting caddycorner from the bar where he used to drink his single-malt scotch looking out over the panoramic views of the bay.

Having admired Mailer (warts and all) for many years, I enjoyed spending a week in his old living room in the company of other writers, working out our various kinks while sitting caddycorner from the bar where he used to drink his single-malt scotch looking out over the panoramic views of the bay.

In the workshop we explored how to weave historical context into a story, with Mailer himself providing the context for the week (grounding our discussion in Armies of the Night).

It's been four years since Mailer passed away, but the man's presence felt as pervasive as the sea air drifting in through the windows. Mailer's biographer Mike Lennon joined us on the first afternoon to share stories of his 40 year friendship with Mailer, walking us around the house where his books were still on the shelves, his paintings on the walls, and his piles of notes sitting on his desk just as he left them.

Mailer distrusted technology, and his attic study reflects that conviction: with no sign of a computer or even a typewriter (though he did have a perfunctory fax machine in the back of the room). Nor did he allow himself an air conditioner even in the sweltering summer heat (Lennon explained that Mailer disliked air conditioners as much as he disliked word processors, preferring to "sweat it out" while he wrote everything out in longhand).

On the last night we gathered for a cocktail party on the deck overlooking the bay, followed by a late dinner at Shay's, one of Mailer's longtime haunts. Over beer and lobster we had the good fortune of meeting a server who had waited on Mailer's table for some two decades. She shared her recollections of the man, who in his later years apparently developed a rabid fondness for oysters, as a tonic for the once-Priapic novelist's shrinking member. She told us how Mailer and his wife Norris would pore over the oyster shells after they ate them, as though reading tea leaves, looking for the likeness of faces in the shells. When they found an auspicious shell, they would take them home and collect them in a glass vase back at the house, where they sit to this day.

The waitress also told us how Mailer got crankier as the years went by, in the way that old men do. One had the sense of someone describing a beloved but cantankerous old uncle: a man she clearly admired and yet often found exasperating. Which, come to think of it, is about how I feel about Mailer too. The man was a near-genius capable of prophetic revelation. Yet, like Henry Miller, he was also capable of incredibly bad writing and susceptible to moral lapses. His greatest successes were often followed by painful personal failures. As Lennon put it, he lived in close contact with his contradictions, always in touch with what he called "the minority within."

Perhaps this why I have always felt so drawn to Mailer. For me, he provides the context of a writer who embraced his imperfections, sometimes transcending them, sometimes flaming out in spectacular fashion, but always persevering, sweating it out to the end.

84000

June 13, 2011

For the past several months, I've been working with a team of talented volunteers to launch 84000: Translating the Words of the Buddha, a new global initiative to translate the Tibetan Buddhist canon into English.

Given the widespread popular interest in Buddhism in recent years, I was surprised to learn that fewer than 5% of classical Tibetan Buddhist texts have ever been translated into English. With the continuing decline of classical Tibetan in the wake of the post-1959 Tibetan diaspora, there is a real risk that some of these powerful teachings may be lost to posterity unless we act quickly to preserve them.

This project stemmed from an international translators' conference, convened in 2009 by Dzongsar Khyentse Rinpoche. Since then, an extended team of teachers, translators and scholars have been working hard to get the effort off the ground. The current Web site is just the first step in a more ambitious untertaking to build an online "reading room" that will allow Web visitors to peruse the collection of translated texts as they become available over the next few years.

There's much more to be done, but thanks to my fellow volunteers (with a special shout-out to the folks from Milton Glaser's office and Hot Studio), I'm happy to report that the project Web site is now up and running:

84000: Translating the Words of the Buddha

Science Friday

January 9, 2011

As a longtime fan of NPR's Science Friday (dating back to my days stuck

in Bay Area traffic listening to KQED), I was pleased to join this week's show to talk about my article on citizen science in last week's New York Times.

Citizen Science

December 28, 2010

Today's Times is running my article on citizen science, exploring the impact of public Web-based participation on scientific research. This is a big topic, one that was difficult to do justice within the confines of a newspaper article. Still, it's been interesting to follow the lively discussion in the comments about who should or shouldn't be allowed to claim the mantle of "scientist." In my view, this is very much an open question, one that will likely to continue to generate debate as more and more people get involved in participatory science projects.

It's worth noting, however, that citizen science has a long heritage predating the Web. In the US, folks like Ben Franklin, Thomas Jefferson and James Audubon all made substantial contributions to science without holding formal appointments as quote-unquote scientists. Many thousands of private citizens have participated in the Audubon Society's annual Christmas Bird Count for more than a century; and there are many other examples of collaboration among scientists and civilians. Professor Patrick McCray of UC-Santa Barbara wrote in to alert me to his book Keep Watching the Skies!, which documents the long collaboration between Moonwatch and professional astronomers.

While researching the piece, I also came across a number of fascinating projects that it simply wasn't possible to cover in one article. For anyone who's interested in exploring the topic further, here are a few additional pointers:

Science for Citizens

A clearinghouse of citizen science projects maintained by Discover magazine's Darlene Cavalier and science journalist Michael Gold.

World Community Grid

Software that lets Web users dedicated their spare computing cycles to a wide range of grid computing projects, a la SETI@home

Citizen Science Alliance

A consortium of projects including Galaxy Zoo, Moon Zoo, and Solar Stormwatch

There are hundreds of other emerging citizen science projects out there, and undoubtedly many more to come in the years ahead.

Update (12/29):

David Weinberger writes a follow-up post, clarifying some of the nuances of his position regarding whether citizen scientists are performing the work of scientists vs. "scientific instruments." Meanwhile, Galaxy Zoo's Chris Lintott writes along the same lines, pointing out that many credentialed scientists spend a great deal of their time performing repetitive tasks not so different from the tasks performed by many citizen scientists. They both make strong arguments that the lines between citizens and scientists are only likely to grow more blurry in the years to come.

MoMA Apps

November 4, 2010

For my research methods class at SVA this semester, I asked the students to develop a series of prototype smartphone apps

for the Museum of Modern Art, based in part on a field study of

museum visitors. The main purpose of this exercise was to explore using

research techniques for concept generation, incorporating techniques

like interviewing, observation and shadowing, KJ analysis, persona

creation, iterative prototyping and usability testing.

For my research methods class at SVA this semester, I asked the students to develop a series of prototype smartphone apps

for the Museum of Modern Art, based in part on a field study of

museum visitors. The main purpose of this exercise was to explore using

research techniques for concept generation, incorporating techniques

like interviewing, observation and shadowing, KJ analysis, persona

creation, iterative prototyping and usability testing.

Coincidentally, just as the students were entering the design phase, Ed Rothstein of the Times wrote a sharp critique of museum mobile apps,

arguing that many current museum apps demand too much attention of their

users,

effectively competing against the art on the walls. After evaluating several apps

from MoMA and elsewhere, Rothstein wrote that he

"felt used along the way, forced into rigid paths,

looking at minimalist text bites, glimpsing possibilities while being

thwarted by realities." The critique struck a chord with several of the

students, some of whom made it an explicit goal to address Rothstein's critique by developing apps that add value to the museum experience without making excessive claims on users' attention.

Considering that the students had to take these projects from research

to prototype in six weeks, I'm impressed with how well they turned

out. Even though each team started with essentially the same material - direct observation of museum visitors - they managed to come up with a series of original and well-differentiated concepts that they were able to prototype with reasonable fidelity within a highly compressed design cycle.

For the final class presentation, we assembled a panel of guests from MoMA to

review and provide feedback on the projects. The judges seemed

genuinely impressed (I'd like to think not just because of the

free wine), and we enjoyed a lively discussion afterwards. All in all, a productive few weeks. Congrats again to everyone involved.

> MoMA Smartphone Apps

Robert McKee

October 14, 2010

There's a Buddhist saying that the best way to make quick progress is to study with a wrathful teacher. For the past four days, I have been studying with the delightfully wrathful Robert McKee, perhaps best-known as the inspiration for Charlie Kauffman's caricature in Adaptation.

In person, McKee seems to get a kick out of playing off his curmudgeonly reputation. A self-described "Stalinist" lecturer, he fines anyone $10 per cell phone ring or texting incident (he recently expelled the CEO of Icelandic TV from one of his seminars for texting in class once too often), chastising students who interrupt him, and peppering about every third sentence with a heartfelt profanity ("and if that offends you," he advises at the outset, "there's the fucking door").

Lesser teachers could never get away with this stuff, but for McKee all this bluster merely has the effect of focusing your attention as he delivers his lectures over four marathon 10-hour days, standing on stage against a black backdrop, no Powerpoint, barely any notes, just a microphone and a plastic coffee mug that he perpetually refills from a black plastic thermos.

It all makes for a hell of a performance. He's been teaching the same course for almost three decades now, and has clearly memorized just about every line. But his delivery never feels rote or formulaic - rather, it all feels like a perfectly rehearsed soliloquy.

His subject matter has been well-chronicled elsewhere, most fully in his 2000 book Story: Substance, Structure, Style and The Principles of Screenwriting. The class itself amounts to a step-by-step recapitulation of his book, laying out his well-developed theory of what makes for effective story-telling: the calculus of beats, scenes, sequences, and acts that make for compelling narrative. I won't attempt to summarize 30 hours worth of lectures here, but I will say that the popular image of McKee as a salesman for formulaic story-telling is entirely unfounded. He is an advocate of form, yes, but not formula. For a sense of the subject matter you can peruse the course outline here.

He makes his case with copious examples drawn primarily from twentieth century films. There must have been more than 100 different references, but here I will share just the ones that are making it into my Netflix cue: Tender Mercies, The Bostonians, Quartet, The Cabinet of Dr Caligari, John and Mary, Mrs Soffel, Ordinary People, In the Realm of the Senses, The In-Laws, The Lavender Hill Mob, Grand Illusion and Y Tu Mama Tambien.

The hands-down highlight of the class came on day four, when McKee took the class through a six hour, scene-by-scene screening of Casablanca, which he considers the apogee of cinematic story-telling. He knows every scene in minute detail, explicating the six interwoven sub-plots, the interlocking visual language systems, and the mythological themes that propel the story forward. In the end, he tied it all together with a piercing and moving final analysis that left half the audience in tears and everyone rising to give him a well-deserved standing ovation.

Here's looking at you, Bob.

Project: Interaction

September 25, 2010

Congrats to my former SVA students Carmen Dukes and Katie Koch on the launch of Project: Interaction, a new initiative to teach interaction design in New York City high schools.

This project had its genesis last semester, when they undertook some ad hoc research into how design skills were being taught at secondary schools (short answer: they're not). I was happy to introduce them to Katherine Schulten at the Times Learning Network, who helped give them some additional pointers on observing teachers and how they engage students in the classroom.

They've been plugging away over the summer to work out the mechanics of the program (see the syllabus), and now the project is officially underway with a little help from Kickstarter. If you like what they're doing, why not throw them a bone?

Q&A with Nick Carr

July 13, 2010

I recently reviewed Nick Carr's new book The Shallows for Interactions (which, alas, requires an ACM subscription to read online). To accompany the piece, I also conducted a brief Q&A with Carr, which I'm taking the liberty of reprinting here.

Welcome Colin

June 26, 2010

It's been a busy week in these parts, ever since my wife gave birth to a beautiful baby boy named Colin. He was born at 3:44 pm on Monday June 21 (the longest day of the year, as my wife can attest), 8lb 9oz and ready for trouble. Everybody is doing just fine.

MFA student project review

April 19, 2010

For the last four months, I've been teaching a class in research methods at the School of Visual Arts' new MFA program in Interaction Design (which partly explains the glacial pace of posting around here lately). As the semester draws to a close, the students are getting ready to show the fruits of their labors at a semi-public presentation next Thursday 4/29 at SVA (132 W 21 St, 6th floor). Anyone who's interested is welcome to attend; we ask only that you RSVP to interactiondesign@sva.edu. Hope to see you there.

Now available for pre-order:

Cataloging the World:

Paul Otlet and the Birth of the Information Age

by Alex Wright

A “shrewd, brisk biography.”

—Kirkus Reviews

GLUT:

Mastering Information Through the Ages

by Alex Wright

“A penetrating and highly entertaining meditation on the information age and its historical roots.”

—Los Angeles Times